My Farewell to Count Tolstoy

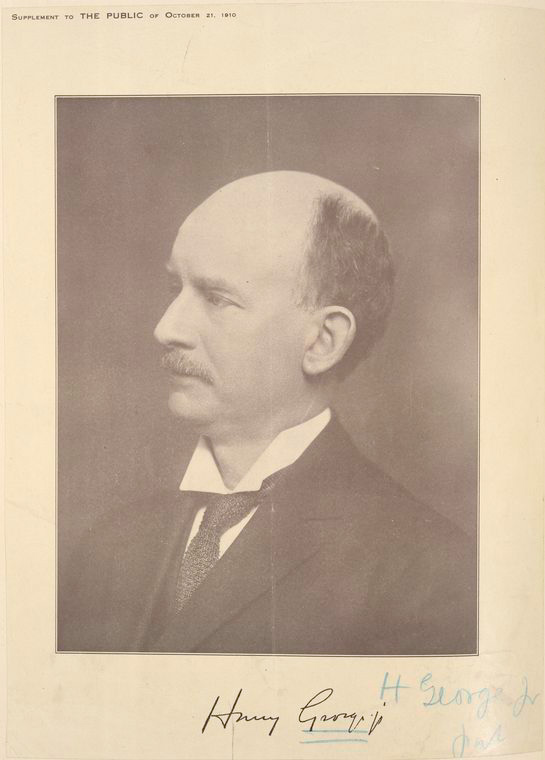

Henry George Jr.

[Reprinted from The World Magazine, 14

November, 1909]

When I said to the chef de train, through an interpreter, that I

wished to send a telegram to Count Tolstoy his face showed at once

surprise and pleasure. He lightly touched his cap and bowed his ready

acquiescence.

This as on the International Express, the crack train that runs once

a week on the Trans-Siberian line, and that carries you from Harbin,

in North Manchuria, where I had got on, to Moscow in nine and a half

days.

It was soon whispered about the train that I was going to drop off at

Toula, a night's ride east of Moscow, to visit Tolstoy - that I had

had an invitation from the great Russian himself.

The surprise and something else I had noticed on the countenance of

the train master I observed on that of the others. It was the tribute

of respect that the name of "Tolstoy" called forth -

deference for the great moral influence of this man, who, despite the

power of Russian church and state, denounces their tyranny over men's

minds and bodies.

"Going to see Tolstoy" I found to be a kind of passport

with high and low; only in the Russian style they do not speak of him

as "Tolstoy," but as "Lyoff Nikolajevitch," the "Tolstoy"

being dropped from common use. Still it is recognized by the more

educated of those you meet.

One of my fellow travelers when he heard of my intended visit asked: "What

kind of a man is Tolstoy?"

I could not definitely answer the question. I had heard so much that

was in a confusion about him. So varied were his writings, like the

many facets of a diamond, and so different and contradictory the

reports of him, that I, in common with many who had been moved and

influenced by his utterances, was floating in judgment as to the man

himself. In one of the standard encyclopaedia sketches I had seen it

gravely stated that the great Russian in his later life had so given

himself up to "mystical and philanthropic ideas … that it

has been doubted whether he is to be regarded as perfectly sane."

But the doubt was dissipated when I came face to face with the

wonderful old man on his ancestral estate, "Yasnaya Polyana,"

meaning "a clearing in the woods." From the moment I met the

venerable man, now eighty-one, he did not seem hard to understand.

Born an aristocrat, he had come to realize that aristocracy is a

fruit of social injustice, which he repudiated, proclaiming equal

natural rights for all.

Born to purple and fine linen, and receiving an early training in the

army and in letters, he had come to shun the vanities of life, to

perceive the highest good in peace and to take to farm labor and the

cobbling of shoes, not merely for the physical benefit of bodily toil,

but for its usefulness and humility.

Raised in the state religion that was but a husk of form and ritual

to the intellectual mind, with no kernel of real faith, his soul went

through the tremendous convulsions of getting the real, burning

religion of loving his neighbor as himself.

Rolled up with the poet and philosopher, the idealist and romancer,

were the practical man and hard intellectual worker, the historian who

sees the past laid plainly before him, and the leader of a people who

would raise the super-structure of a moral society upon just economic

foundations.

It was the many-sidedness, the broadness and loftiness, the poetry,

fervor, simplicity, strength, calmness and unutterable conviction of,

say, a Moses; who indeed, to the superficial, might be doubted to be "perfectly

sane."

Much of this appeared within the first few minutes after I had been

ushered into the Count's work room at Yasnaya Polyana. Among his books

I found him, seated in a wheeled chair, which he had come to use for

rest since an illness of seven or eight years ago. His gray hair and

beard were long and flowing. He wore a loose tunic, or cassock, that

came down to the ankles over high-legged boots, although as he sat his

feet to the knees were covered by a blanket.

He gave me something of the affectionate greeting he would have given

my father had they ever met. For when they had planned to meet my

father's death intervened. In welcoming me the Count said, with almost

child-like simplicity: "Your father was my friend."

That bond, so far as Count Tolstoy was concerned, began years before

- in 1884 - when my father had published his second of his larger

books. County Tolstoy subsequently wrote about it to Herr Eulenstein

of Berlin, an intense Single Taxer, who inquired what the Russian

philosopher thought of the American's teachings. Among other things

Tolstoy said in that letter:

"I have known Henry George since

the appearance of his Social Problems. I read it and was

struck with the correctness of its fundamental thought, its

extraordinary clearness, which is lacking so much in scientific

literature; its common sense, its power of analysis and,

particularly for scientific literature, the exceptional Christian

spirit with which the whole book is permeated. When I had finished

this book I then read his earlier work, Progress and Poverty,

and learned to appreciate still more what Henry George has

accomplished."

With these feelings toward the writings of the father, was it

remarkable that Tolstoy should have given a cordial welcome to the

son?

And in talking with him over a great range of subjects it was obvious

that this man, with an aged, delicate body, had a soul of youth. He

revealed the liveliest knowledge of what was going on over the world

and made the keenest comments, drawing the general conclusion that the

great struggle for the overthrow of industrial slavery in the world

will end in victory, just as the chattel slavery struggle in the

United States and Russia half a century ago ended.

"This is the thing that the Count is constantly speaking of,"

said Countess Tolstoy when I chanced to sit apart with her and from

the others after supper.

I was extremely interested to meet the Countess, about whom also I

had heard so much. Some had said that she was not in sympathy with the

views and teachings of her great husband. I could see no indications

of this. The utmost harmony prevailed, although I am informed that,

desiring to give the freest possible circulation to his views, the

Count agreed that his wife and children were to have the copyrights of

his earlier writings, being chiefly the novels, while he was to be at

liberty to print upon all his later writings the words: "No

rights reserved," giving the world at large the right to publish

them. And these words appear upon "The Great Iniquity" and

other of his incomparable works.

As I said beside the Countess, looking over a Kodak album of family

pictures, my hostess being engaged in fancy sewing, I asked about the

number of children.

"I have had thirteen children," she answered in the best of

English. "I have seven living and twenty-nine grandchildren."

Notwithstanding this the Countess is a remarkably well preserved

woman. She is actually but sixty-four. She constantly studies the

material welfare of her famous husband.

What was of much personal moment was that the Countess assured me

that the County every day talked of my father. And, indeed, I found

that he not only talks of him constantly, but that he promotes the

circulation of the Henry George books, of course translated into the

Russian tongue. He presents their doctrines as the economic basis of

is own moral philosophy of loving thy neighbor as thyself.

I offer two brief letters to witness this out of a volume of recent

correspondence, omitting names, of course.

"Mr. T.A.: ----, United States.

"Dear Sir - I received your letter and a copy of your book,

-------. I am very much astonished to find that an American,

discussing the land question, does not make any allusion to Henry

George and his great theory, which alone solves completely the land

question. Your very truly, LEO TOLSTOY, May 18, 1909

The other letter ran:

"To the Land Rehabilitation

Society, Japan.

Dear Gentlemen - Please excuse me for not answering your letter for

so long a time. The best help I can give you is to draw your

attention to the great American writer, Henry George, and his theory

on the land question, which is expressed in the book I send you,

Progress and Poverty. LEO TOLSTOY, May 187, 1909

Perhaps it was natural that he should think of my father as I bade

him adieu. He took my hand and said simply: "This is the last

time I shall meet you. I shall see your father soon. Is there any

commission you would have me take to him?"

When I found words I said: "Tell my father that I am doing the

work."

His response was a silent nod, and I left him.

|