The Georgist Philosophy

in Culture and History

Pat Aller

[July, 1999]

The Georgist Philosophy in Culture and History: How to Broaden Our

Focus to Strengthen Our Message.

We've been asking this question for over a century.

The very fact that we are in Arden attests to George's influence

on culture in his day. As you've already heard, artists founded this

place. The maker's marks of Frank Stephens, Will Price, and others

are everywhere here. Sculpture by Stephens was also in

Philadelphia's City Hall. I don't know if it's still there, but we

have his poems, one of which I'll read later.

George, in his lifetime, influenced many other artists, the most

famous being Leo Tolstoy and George Bernard Shaw. Tolstoy arranged

for, and possibly financed, the translation of all George's books

into Russian, using cheap editions to educate his former serfs and

writing the foreword to the Russian edition of Social Problems.

And in his own book, Resurrection, Tolstoy incorporated

George's idea of land as birthright. This is the book for which the

great Russian was excommunicated from his church and which was

censored in early European and English translations, deleting

references to George and to Herbert Spencer.

Shaw says hearing and reading George made a man of him. He adds

that five-sixths of Britain's Fabian socialists, including Beatrice

and Sidney Webb, were catalyzed into action by George's ideas. The

fine book edited by Dorothy and Will Lissner, George and

Democracy in the British Isles, mentions many others.

Continental Europe was also reading George in his time, as the

Lissners' forthcoming Henry George in Europe will attest. So were

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South America, and, later, China.

Charles Albro Barker, author of the authoritative biography, Henry

George, published by Oxford University Press, sees the legacy of

Georgism as fiscal, political, and moral. It is the moral, or

philosophical, on which I concentrate, as evidenced in culture, or

the arts. In the interest of time and relevance, I include only

United States artists, by whom I mean all connected with painting,

photography, architecture, and sculpture; with music; and with

writing -- poetry and prose, including nonfiction, in books, radio,

film, and television. Although I'd like to limit works to those by

people who knew George or his writings, I'll cite others of social

protest who support ideas like George's, when I reach the time when

his influence waned. I omit economists, most politicians, and living

Georgists. I'll go light on history, since many of you know it well.

As for how to broaden our focus, I hope our discussion will provide

some answers. My purpose is to share with you names and works of

Georgists and others whose art, pleading for social justice, can be

used to attract a wider audience to our cause.

There are nearly 125 years of Georgist history between the

publication of Progress and Poverty in 1879 and today. To

give those years some form, I divide them into three periods: 1879

to 1929 (the beginning of the Great Depression), 1929 to 1945 (the

end of World War 11), and the last fifty years. George's book was

published during an era of massive industrialization, encompassing

railroad expansion, factory work, and huge foreign immigration to

the cities. He was not the only one appalled by the contrast between

the robber baron and the worker or tramp, but the strength of his

ideas and style helped others hone their perspectives on his words.

While none had the stature of Tolstoy or Shaw, they had wide

influence, some still admired today.

Of George's influence in the United States, Barker writes: "By

the middle 80s surges of acceptance and rejection delighted or

dismayed Americans, according to their sentiments. Then gradually

his ideas worked their way into the deeper strata of public thought

and conscience. When Georgism seized minds of legalistic bent, like

Thomas Shearman's, it impelled me single- tax movement, which began

during 1887 and 1888 in New York. When it seized practical and

political minds, Tom Loftin Johnson's most notably, Georgism entered

near its source the stream that later broadened to become the

progressive movement of the twentieth century [subject of a

forthcoming book in the George Series, edited by the Lissners].

When, at their farthest reach, the ideas of Henry George engaged

literary and philosophical minds, such as George Bernard Shaw's and

Leo Tolstoy's abroad, and Hamlin Garland's and Brand Whitlock's in

the United States, the moral appeal of Progress and Poverty

extended with added charm beyond the circle of those who had read

George's books or listened to his lectures or joined organizations,

and had pondered his argument for themselves. No other book of the

industrial age, dedicated to social reconstruction and conceived

within the Western traditions of Christianity and democracy,

commanded so much attention as did Progress and Poverty."

That's what we're looking for -- to go beyond our circle.

"[T]he axioms of [George's] thought were always the same,"

continues Barker. "They were the Jeffersonian and Jacksonian

principles of destroying private economic monopolies and of

advancing freedom and equal opportunity for everyone."

Progress and Poverty was one of 13 books that changed

America, according to Eric Goldman, writing in The Saturday

Review in 1953. The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens,

the muckraking author influenced by George, was another. And a third

was Human Nature and Conduct by John Dewey, who held George

in such esteem that he served as an honorary officer of the Henry

George School, was founding advisory editor to The American

Journal of Economics and Science, and in 1933 broadcast an

appeal to President Franklin a Roosevelt to adopt a national land

value tax to ease the financial crisis.

Henry Steele Commager writes, in The American Mind:

The decade of the nineties is the watershed of American

history. As with all watersheds the topography is bluffed, but in

the perspective of half a century the grand outlines emerge clearly.

On the one side lies an America predominantly agricultural;

concerned with domestic problems; conforming, intellectually at

least, to the political, economic, and moral principles inherited

from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries -- an America still in

the making, physically and socially; an America on the whole

self-confident, self-contented, self-reliant, and conscious of its

unique character and of a unique destiny. On the other side lies the

modem America, predominantly urban and industrial; inextricably

involved in world economy and politics; troubled with the problems

that had long been thought peculiar to the Old World; experiencing

profound changes in population, social institutions, economy, and

technology; and an to accommodate its traditional institutions and

habits of thought to conditions new and in part alien.

[T]he demands made upon the integrity of the American character

and the resourcefulness of the American mind at the end of the

century were more complex and imperative than at any time in a

hundred years ... of class conflict in American society, and the

fashioning of new legal and political weapons for that struggle

.... The great issues of the nineties still commanded popular

attention half a century later.

Another critic commented that one of the "major principles of

that new economic thought which was to become the orthodoxy of the

twentieth century, appreciation of the relevance of ethical as well

as scientific considerations... found expression in the hopeful and

not wholly futile effort to Christianize and humanize the social

order which enlisted the efforts of ... that large and straggling

body of reformers from Henry George to Henry Wallace who sought to

subordinate economic to social ends."

"The literature of the post[Civil]war years" [returning

to Commager] "had been regional and romantic; that of the

nineties was sociological and naturalistic .... The Thirteenth

District [Georgist Brand Whitlock's novel] owed much to Altgeld

and "Golden Rule" Jones, but more to Brand Whitlock's own

experience in Toledo ward politics.... The Saturday Evening Post

... published such novels as Frank Norris' The Octopus.

Willa Cather, Ellen Glasgow, Edith Wharton, Theodore Dreiser, Brand

Whitlock, Thomas Beer, and Sinclair Lewis appeared in its hospitable

pages."

A poet who galvanized the conscience of the 90s was Edwin Markham,

whose "The Man with the Hoe" is still included in

anthologies. He wrote it after seeing Jean-Francois Millet's

painting by that name. Like another great painter, Francisco Goya

(whose searing sketches of the poor are on exhibition, temporarily,

right around the comer at the Philadelphia Museum of Art), Millet

saw the roots, the radical truth behind pastoralism so often

portrayed sentimentally. Markham's poem first appeared in 1899 in

the San Francisco Chronicle, which printed many a piece about that

city's Henry George:

The Man With the Hoe by Jean-Francois

Millet

Bowed by the weight of centuries he leans

Upon his hoe and gazes on the ground,

The emptiness of ages in his face,

And on his back the burden of the world.

Who made him dead to rapture and despair,

A thing that grieves not and never hopes,

Stolid and stunned, a brother to the ox?

Who loosened and let down his brutal jaw?

Whose was the hand that slanted back this brow?

Whose breath blew out the light within this brain?

Is this the thing the Lord God made and gave

To have dominion over sea and land,

To trace the stars and search the heavens for power,

To feel the passion of Eternity?

Is this the dream He dreamed who shaped the suns

And pillared the blue firmament with light?

Down all the stretch of Hell to its last gulf

There is no shape more terrible than this--

More tongued with censure of the world's blind greed--

More filled with signs and portents for the soul--

More fraught with menace to the universe.

What gulfs between him and the seraphim!

Slave of the wheel of labor, what to him

Are Plato and the swing of Pleiades?

What the long reaches a the peaks of song,

The rift of dawn, the reddening of the rose?

Through this dread shape the suffering ages look.

Time's tragedy is in that aching stoop.

Through this dread shape humanity betrayed,

Plundered, profaned and disinherited.

Cries protest to the judges of the world.

A protest that is also a prophecy.

0 masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

Is this the handiwork you give to God,

This monstrous thing distorted and soul-quenched?

How will you ever straighten up this shape,

Give back the upward looking and the light,

Rebuild in it the music and the dream,

Touch it again with immortality,

Make right the immemorial infamies,

Perfidious wrongs, immedicable woes?

0 masters, lords and rulers in all lands,

How will the future reckon with this man?

How answer his brute question in that how

Men whirlwinds of rebellion shake the world?

How will it be with kingdoms and with kings--

With those who shaped him to the thing he is--

Men this dumb terror shall reply to God,

After the silence of the centuries?

Another poet, famous for her tribute to the Statue of Liberty, is

Emma Lazarus, who corresponded with George. Here is her poem, "Progress

and Poverty," first published in The New York Times in

1881:

Oh splendid age when Science lights her lamp

At the brief lightning's momentary flame,

Fixing it steadfast as a star, man's name

Upon the very brow of heaven to stamp!

Launched on a ship whose iron-cuirassed sides

Mock storm and wave, Humanity sails free,

Gayly upon a vast, untrodden sea.

O'er pathless wastes, to ports undreamed she rides,

Richer than Cleopatra's barge of gold,

This vessel, manned by demi-gods, with freight

Of priceless marvels. But where yawns the hold

In that deep, reeking hell, what slaves be they,

Who feed the ravenous monster, pant and sweat,

Nor know if overhead reign night or day?

Commager explains,

[T]he dominant trend in literature was critical; most

authors portrayed an economic system disorderly and ruthless,

wasteful and inhumane, unjust alike to workingmen, investors, and

consumers, politically corrupt and morally corrupting. ... Never

before in American literature and rarely in the literature of any

country had the major writers been so sharply estranged from the

society which nourished them and the economy which sustained them as

during the half-century between The Rise of Silas Lapham and Grapes

of Wrath [L]iterature was not only an echo but often -- as with The

Jungle -- a trumpet and an alarm. During the Populist era it was

Howells and Garland, Norris and Frederic, who set the literary tone;

those who were not championing the cause of the farmer were pleading

the rights of labor or designing Utopias -- some fifty of them

altogether during these years -- to show what felicity man might

achieve if only economic competition were banished.

Of those American writers affected directly by George, by knowing

him or his book, one of the greatest was Hamlin Garland. From the

Middle West, where his parents farmed unsuccessfully, he moved East,

where he saw how banking, as much as trade, determined farmers'

fates. Main-Traveled Roads (a collection of short stories), novels,

and a series of reminiscences about the Middle Border (as he called

the Middle West) are his heritage. "Under the Lion's Paw"

describes how a man saving to buy the farm he has worked for three

years finds himself in a Catch-22 because he has improved it.

Butler, the landlord, speaks to Haskins, his tenant farmer:

"Oh, I won't be hard on yer. But what did you expect

to pay f'r the place?"

"Why, about what you offered it for before, two thousand five

hundred, or possibly three thousand dollars," he added quickly

as he saw the owner shake his head. "This farm if worth five

thousand and five hundred dollars," said Butler in a careless

but decided voice.

"What! " almost shrieked the astonished Haskins. "What's

that? Five thousand? Why, that's double what you offered it for

three years ago."

"Of course, and it's worth it. It was all run down then; now

it's in good shape. You've laid out fifteen hundred dollars in

improvements, according to your own story."

"But you had nothin' t' do about that. It's my work an' my

money."

"You bet it was; but it's my land."

"But what's to pay me for all my --?"

"Ain't you had the use of 'em?" replied Butler, smiling

calmly into his face.

Haskins was like a man struck on the head with a sandbag; he

couldn't think; he stammered as he tried to say: "But -- I

never 'd git the use-- You'd rob me! More'n that, you agreed -- you

promised that I could buy or rent at the end of three years at--"

"That's all right. But I didn't say I'd let you carry off the

improvements, nor that I'd go on renting the farm at two-fifty. The

land is doubled in value, it don't matter how; it don't enter into

the question; an' now you can pay me five hundred dollars a year

rent, or take it on your own terms at fifty-five hundred, or -- git

out."

He was turning away when Haskins, the sweat pouring from his face,

fronted him, saying again: "But you've done nothing to make it

so. You hain't added a cent. I put it all there myself, expectin' to

buy. I worked an' sweat to improve it. I was workin' f'r myself an'

babes--"

Haskins sat down blindly on a bundle of oats nearby and, with

staring eyes and drooping head, went over the situation. He was

under the lion's paw. He felt a horrible numbness in his heart and

limbs. He was hid in a mist, and there was no path out.

Frank Norris called the Southern Pacific Railway "The Octopus"

in his novel of that name:

The [railroad] map was white, and it seemed as if all the

color which should have gone to vivify the various counties, towns,

and cities marked upon it had been absorbed by that huge sprawling

organism .... It was as though the State had been sucked white and

colorless, and against this pallid background the red arteries of

the monster stood out, swollen with life-blood, reaching out to

infinity, gorged to bursting, an excrescence, a gigantic parasite

fattening upon the life-blood of an entire commonwealth.

Listen now to Henry Demarest Lloyd, who wrote Wealth against

Commonwealth, and was one of the three author-activists who were the

subjects of John L.Thomas's provocative Alternative America:

(Harvard University Press). The others were Edward Bellamy, author

of Looking Backward, and George.

If our civilization is destroyed, as Macaulay predicted,

it will not be by his barbarians from below. Our barbarians come

from above. Our great money-makers have sprung in one generation,

into seats of power kings do not know....Without restraints of

culture, experience, the pride, or even the inherited caution of

class or rank, these men, intoxicated, think they are the wave

instead of float, and that they have created the business which has

created them. To them science is but a never-ending repertoire of

investments stored up by nature for the syndicates, government but a

fountain of franchises, the nations but customers in squads ....

They claim a power without control, exercised through forms which

make it secret, anonymous, and perpetual.

Today David Korten's powerful book, When Corporations Rule

the World, says the same thing, with less eloquence. Norris,

Lloyd, and Bellamy were not Georgists, but shared with them many of

the same protest meetings and utopian conferences. George was asked

to join their Populist ticket but chose not to.

Of the muckrakers, those pioneer investigative journalists, writes

Commager, "Lincoln Steffens was the most astute, and the most

influential. His findings are to be read in the sensational Shame of

the Cities, but it is me sober and disillusioned Autobiography that

best presents his conclusions ... a cold- blooded analysis of how

the political system actually works. Together with such

autobiographies as Tom Johnson's My Story and Brand

Whitlock's Forty Years of It, it swept away the whole case

of the civil service reformers of the Progressive era, for it made

inescapably clear that the political corruption stemmed from

commercial, that bosses were me creatures a big business and the

spoils system the natural product of a predatory economy, and that

the moral approach to politics was not only inadequate but

foredoomed to frustration."

Good nonfiction -- whether a description of events or of a life,

one's own or another's--is art. You have just heard the highest

praise, by Commager, for three Georgists. Steffens is the best

known, but, in the arts of governance, Johnson and Whitlock are

tops. Johnson (like a later Georgist, John C. Lincoln) was an

inventor who grew rich on his patents.

He was introduced to Georgist books by a railroad porter, and became

an admirer and close friend of the author. He was elected to Congress,

then to four terms as mayor of Cleveland, Ohio. You can see his statue

there today, a copy of Progress and Poverty in his hands.

Between George's death in 1897 and the outbreak of World War I in

1914, prominent Georgists, including several writers, influenced

presidents, Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, some attaining

Cabinet or other high office. Whitlock, who was reform mayor of

Toledo, Ohio, later served as ambassador to Belgium as part of the

great Georgist circle around Wilson. Both Johnson and Whitlock

instituted many civic reforms, including demonopolizing municipal

transit and other services. Read all about them, and good governance

in general, in the Lissners' George and Ohio's Civic Revival,

part of their George Series. Whitlock also wrote a novel of social

protest, but here's an excerpt from his autobiography, Forty

Years of It:

I speak of their [Mark Twain's and William Dean

Howells's] democracy for the purpose of likening it in its very

essence to that of Golden Rule Jones and of Johnson [both Georgist

mayors], too, and of all the others who have struggled in the human

cause.

Upton Sinclair's stunning novel, The Jungle, is a

horrifying depiction of industrial brutalization and of indifference

to the public's wellbeing. Such art still raises more anger than a

dozen Ralph Naders, though we need all the Naders we can get.

Sinclair established a utopian community in New Jersey -- Helicon

Hall--which was burned down by a firebomb, as we heard last night.

He spoke up for George many times, lived here in Arden, also in

Fairhope [both Georgist enclaves], and then moved to California,

where he ran for governor and lost.

Robert Heilbroner, in The Worldly Philosophers, says of

George, "[T]he import of his ideas -- albeit usually in watered

form -- became part of the heritage of men like Woodrow Wilson, John

Dewey, Louis Brandeis .... The complacency of the official world was

not merely a rueful commentary on the times; it was an intellectual

tragedy of the first order. For had the academicians paid attention

to the underworld, had Alfred Marshall possessed the disturbing

vision of a Hobson, or Edgeworth the sense of social wrong of a

Henry George, the great catastrophe of the twentieth century might

not Eve burst upon a world utterly unprepared for radical sit

change."

Let's take a break now from wordsmiths to some other kinds of

artists who built American culture. Literal builders, or architects,

of Georgist inspiration or sympathy, include Frank Lloyd Wright,

perhaps this nation's greatest and certainly most daring architect.

He spoke at a Georgist meeting in Chicago in 1951 and praised George

for the "organic" quality of his thought, a rootedness and

wholeness essential to great art. Remembering that the origin of

radical is root, getting to the source of things. we

find George's radical diagnosis of, and remedy for, economic

inequality heeded by Walter Burley Griffin. He was a Georgist, and,

like Wright, a Chicago architect. He won the competition to design

Australia's new capital, Canberra, and provided that its land be

leased, not sold, and taxed on value.

As for painters, few are credited with being Georgists, although

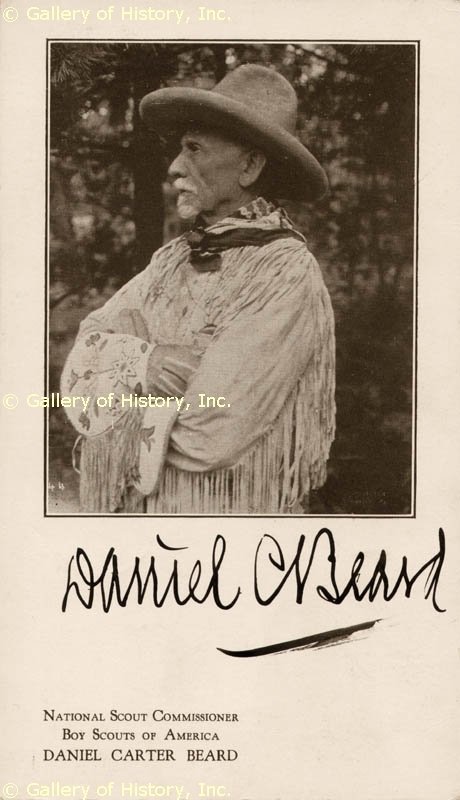

Arden contains exceptions. Daniel Carter Beard, who illustrated Mark

Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, was

another. Twain is said to have remarked that Beard had "made of

my book a Single Tax work," because of its scathing portraits

of vested interests. [The drawing at right is captioned "They

have a right to their view; I only stand to this." --Ed.]

Beard went on to become more famous as leader of the American Boy

Scouts. Amy Mali Hicks, who lived in Arden's Georgist neighbor, the

enclave of Free Acres in New Jersey, was a well-known stage

designer. But for inspiration we have to turn to the artists of the

30s and later, many helped by the New Deal's Federal Arts Project,

who show us poverty and despair in both city and country. They

include George Bellows, Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, Charles

Sheeler, and many others. The project, writes Commager, "was an

expression of the principle that literature and art, music and

drama, were as essential to the happiness and prosperity of the

nation as any merely economic activities, and that those who engaged

in them were legitimate objects of the patronage of the state."

This belief was echoed often by George's famous granddaughter, Agnes

de Mille.

Photography may do even more than painting to unjustify "God's

ways to man." One of the great artists in that field lived when

George did, though I find no acknowledgment by either of the other.

He is Jacob Riis, a Danish immigrant whose images, in The Making

of An American and How the Other Half Lives still

assault us with dark scenes of starvation and crime in New York

City. A superb photographer of our own times and of our land before

we ruined it, Ansel Adams wrote, in the preface to Alexander

Alland's Jacob A. Riis, Photographer & Citizen: [T]he

larger content lies in Riis's expression of people in misery, want

and squalor. These people live again for you in the print -- as

intensely as when their images were captured on the old dry plates

of ninety years ago. Their comrades in poverty and suppression live

here today, in this city -- in all the cities of the world."

Walker Evans' pictures, abetted by the text of James Agee, in Let

Us Now Praise Famous Men, chronicled the bleak lives of five

sharecropper families in the 30s. Dorothea Lange and countless

others did the same, often for federal agencies like the Department

of Agriculture.

For music, let's begin right here in Arden, with Frank Stephens'

Grubb's Corner, to Gilbert & Sullivan melodies. Can you

resist lifting your voices in song to "When First I Came to the

Delaware Shore," to the tune of "The Ruler of the Queen's

Navy" from HMS Pinafore?

Men first I came to the Delaware shore,

It was some weeks ahead of Lord Baltimore,

And I floundered over moor and fen

Some days ahead of William Penn.

I cut my schedule down so fine

That I reached the banks of the Brandywine

Some half an hour or so I claim,

Before these folks from Holland came.

By dropping my kit and hustling quick

I was first to get to Naaman's Creek,

And just ahead of Dutch and Quakers

Mandated some five thousand acres.

And here secure from war's alarms,

I'll stake out hundred acre farms.

I'll rent them fair, as man to man,

And farm the farmers as I can.

And then when Wilmington grows great

We'll make some booms in real estate,

And all by landlord's law will be

For me and my posterity.

Among Georgists I find only those who set their own lyrics to

popular tunes by others. From the larger world, there is the grand

music of Virgil Thomson, enhancing the tough prose of Pare Lorentz

in the film, The Plow that Broke the Plains, which documents

how poor farmers had to keep moving on, from bad soil to worse

(Georgists call it land at the margin), turning the nation into a

vast dust bowl in their desperate attempts to feed their families.

Then there are George Gershwin's melodies and orchestration for

Dubose Heyward's Porgy and Bess, especially a song like "I

Got Plenty 0' Nothin'," although the social message -- the

brutality of poverty -- is muted. The music that speaks our cause

the most, I believe, is folk and the blues. Just two nights ago, I

heard on WQXR radio's "Woody's Children," Odetta, Oscar

Brand, and Tom Paxton. They sing our words. Lindy tells me Bob Dylan

has a number called "Dear Landlord." And nearly all Pete

Seeger's songs are about social justice. (One of our Georgists, Mary

Rose Kaczorowski-Redwood Mary -- spoke to Pete and presented her

views at his popular Clearwater Festival on the Hudson River last

month.)

The anthem of the Depression was written by that clear-eyed tramp,

Woody Guthrie, singing of the out-of-work, out-of-luck,

out-of-pocket, who are no longer such a small number in the United

States. We all know "This Land Is Your Land, This Land Is My

Land". How many know that Australia's unofficial anthem, "Waltzing,

Matilda", about a tramp chased to death by police, was written

by a bona fide Georgist?

Agnes de Mille, George's granddaughter, is a world-class

choreographer who introduced an American idiom in the musical

Oklahoma, bringing to greater fame Aaron Copland, who composed the

music. De Mille is less well known as a great autobiographer -- more

than a half dozen books about her life as well as that of America

and the dance. Funny, heart breaking. Tough, too. Just read her

preface to the centenary edition of Progress and Poverty.

Here's a section:

The great sinister fact, the one that we must live with,

is that we are yielding up sovereignty. The nation is no longer

comprised of the thirteen original states, nor of the thirty- seven

younger sister states, but of the real powers: the cartels, the

corporations. Owning the bulk of our productive resources, they are

the issue of that concentration of ownership that George saw

evolving, and warned against.

These multinationals are not American any more. Transcending

nations, they serve not their country's interests, but their own.

They manipulate our tax policies to help themselves. They

determine our statecraft. They are autonomous. They do not need to

coin money or raise armies. They use ours.

Drama, you'd think, would have had many Georgist practitioners.

Only one play by a Georgist, James Herne's Shore Acres, made

it to the footlights and is not performed today. A few Georgists

wrote some shorter ones, gathering dust in our archives. In the 30s

and later America had social realism -- Elmer Rice, Lorraine

Hansbery (dead too young) of A Raisin in the Sun, Arthur

Miller, and more. Tobacco Road had a long run, as did

Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, both originally novels. The

latter is also a powerful opera, which I saw this year. Another

novel, turned film, and soon to be an opera, is Sister Helen

Prejean's Dead Man Walking, about prisons and capital

punishment. (One of my Henry George Institute students is in the

prison she describes.) Rent, a current drama hit based on

Puccini's opera, La Boheme, has characters who starve and

die, but neither the opera nor the play stirs real outrage.

The Great Depression bared the bones of society. I've just named

many artists of that period. Some great works were created because

of poverty; the WPA -- Works Progress Administration -- employed and

paid people to paint murals in libraries, post offices, and other

public buildings; to collect songs; and to record poverty and

progress through books and photographs.

Commager describes a giant of the 30s and 40s:

If Dos Passos derives from Veblen, John Steinbeck derives

from Henry George. His theme, like that of the great California

radical, is the contrast between progress and poverty, and the

calamitous consequences of the exploitation of the land. More

clearly than any other critic or crusader of the thirties, he

carries on the tradition of revolt and reform established by Hamlin

Garland and Frank Norris, and of the nostalgia for the generation of

the builders and impatience with the generation of the exploiters

that is implicit in so much of Willa Cather.

Grapes of Wrath is more than the story of the flight of

the Okies from the dust bowl to golden California. It is an

indictment of the economy that drove them into flight, that took

the land from those who had tilled it and handed it over to the

banks, that permitted hunger in the land of plenty and lawlessness

in the name of law and made a mockery of the principles of justice

and democracy.

Here is Steinbeck:

The banks worked at their own doom, and they did not know

it. The fields were fruitful, and starving men moved on the roads.

The granaries were full, and the children of the poor grew up

rachitic, and the pustules of pellagra swelled on their sides. The

great companies did not know that the line between hunger and anger

is a thin line. And money that might have gone for wages went for

gas, for guns, for agents and spies, for blacklists, for drilling.

On the highways the people moved like ants and searched for work,

and food.

World War II -- fought, so Adolph Hitler said, for "lebensraum"

(space to live, land) -- brought unspeakable slaughter and

destruction. Man's inhumanity to man is best exemplified by another

example I must take from abroad -- Picasso's Guernica, the

bombing of that Spanish city by fascists in 1937. The victims were

Basque separatists protesting an oppressive Spanish government,

which turned to Germany for its dirty work. We are taught that World

War 11 began in 1939, but me kindling had already been lit in Spain,

in Ethiopia, and in other places suffering social injustice.

War, as always, creates jobs and wealth for some, and a "just"

war dampens social protest. America's communist "enemy, "

Russia, became a friend for awhile. After the war prosperity came to

most in the United States. The GI Bill (free college education with

living expenses for veterans) brought culture to many who'd never

had time or money for it. GI loans bought houses for the masses, not

always pretty, as Malvina Reynolds sang in "Little Boxes".

New towns sprawled into farm land and wet land and forest land. The

growing isolation and indifference of people were characterized in

Frank Reisman's chilling sociological study, The Lonely Crowd.

The millennium approaches, with the great Jubilee 2000 to be

celebrated by religious denominations worldwide. Georgists have

potential allies there. We share their aims of economic justice and

George was a major influence on religious leaders. There is no time

today to include that part of our culture, but I recommend Robert

Andelson's son's works on the subject, especially From Wasteland

to Promised Land. And I remind you that three major New York

City religious leaders knew and admired George: Stephen Wise, after

whom the Free Synagogue is named; John Haynes Holmes, eloquent

minister of the Community Church (Unitarian); and Edward McGlynn, of

St. Stephen's, excommunicated from the Catholic Church for his

support of George.

As I close, I've cheated you on the most recent 50 years, and on

history. There are, in those years, the same social problems --

civil rights, poverty, war. And some splendid artists communicating

them. But while creative people in other nations have had much to

say on the issues of land and monopoly, I find less emphasis by

United States artists -- until recently. I believe, however, we're

in a new era where essayists and journalists (print, radio, TV,

film, the web) are showing greater awareness. We had Edward R.

Murrow's "The Harvest of Shame" on TV. Today we have Alan

Durning, David Hapgood, Michael Kinsley. Did you know Fairhope's

Paul Gaston was a consultant to National Public Radio's recent

series on the civil rights movement of the 60s? Alanna Hartzok

brought the young novelist of Appalachia's poverty, Denise Giardina,

to address our 1989 sesquicentennial Georgist conference in

Philadelphia.

Ken Burns is doing another TV documentary, this one on American

feminism. Let's hope it's not too late to let him know that Carrie

Chapman Catt (who was a possible presidential candidate) and other

Georgist women, like "Alaska Jane" McEvoy, were active for

women's right to vote, as was George.

I've listed, in a separate paper, more than 300 Americans eminent

for both their compassion and their culture since George's day. Let

us cite them, quote them, use them. We have allies in the widest

spectrum of interests. We are for the single tax -- but let us not

continue in a single band of the spectrum towards it.

I close with a Georgist poet, E. Yancey Cohen, one of the

Schalkenbach Foundation's original directors, who wrote "Jubilee"

in 1928 for a City College of New York class's 50th anniversary

nearly a century ago. It fits our conference on education too.

"The Earth is Mine," thus spake the Lord,

"Sojourners ye by my accord.

Six days for labor, one for rest,

This of my rulings is the best.

The waters of the open sea

For all my children's use are free.

The early and the latter rain

I cause to fall each year again.

The sun's all-generous warmth and glow,

Which from the seed-time makes to grow

The varied harvests of your toil

Give each his corn and wine and oil.

Partake of all my bounteous aid

But let my mandates be obey'd.

Not seek ye field on field to join

Nor others' labors to purloin.

Your heads to think, your hands to do

In fitting way I give to you--

But all my natural Universe,

In which my Godhead I immerse,

My winds, my fires, my powers divine

Shall not be own'd by you -- they're mine!

And woe to those who in their pride

By my great law will not abide!

With equal right use ye the Earth,

This guerdon comes to you at birth--

But he who filches this clear right

Him will I shatter in my Might!"

Thus was the blast of that wild horn

On Palestinian echoes borne.

So seven times seven the years went by,

And we have liv'd and we can die--

But what we've seen and we shall see

Is the bright gold of Destiny.

Sound high, thou horn of Jubilee!

Ring out, 0 bells of Liberty!