Some Questions Have Many Answers:

Niels Bohr on Learning

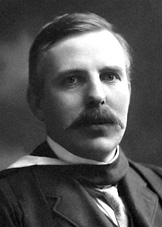

Ernest Rutherford

Several years ago,

SCI added the story that follows below to its online library.

Unfortunately, the source of the story was not captured and is

now lost. A biographical sketch of Bohr states: "In 1911,

Niels Bohr earned his PhD in Denmark with a dissertation on the

electron theory of metals. Right afterwards, he went to England

to study with J.J. Thomson, who had discovered the electron in

1897. Most physicists in the early years of the twentieth

century were engrossed by the electron, such a new and

fascinating discovery. Few concerned themselves much with the

work of Max Planck or Albert Einstein. Thomson wasn't that

interested in these new ideas, but Bohr had an open mind. Bohr

soon went to visit Ernest Rutherford (a former student of

Thomson's) in another part of England, where Rutherford had made

a brand-new discovery about the atom."

In November of 2008, SCI received the note immediately below

regarding the authenticity of the story attributed to

Rutherford.

|

Ernest Rutherford

|

A colleague just pointed me to the rather amusing story about how

Rutherford was involved in Bohr's early education in physics -- you

know, the barometer story that you publish on your site.

I find it highly amusing that a site that claims to teach people to

search for the truth publishes a story that is so obviously a hoax.

Niels Bohr was born in 1885 and got his doctorate at University of

Copenhagen at age 26 in 1911. His entire university (college) carreer

up to that point was in Copenhagen. It seems reasonable to assume he

started college some time in 1903-05. Possibly as early as 1900, but I

find it hard to believe it was any earlier than this.

Rutherford was appointed chair of physics in Montreal, Canada in

1898.

Here he did the work that earned him the nobel prize in chemistry

1908. In 1907 he took the chair of physics at Manchester University.

It seems a tad unlikely that Rutherford would ask a common student to

travel the atlantic (or even to England) for a rather silly physics

problem -- also it seems unlikely that Bohr in the later part of his

studies should be given such a problem at all, so the 1907-1911 period

is highly unlikely.

The story claims that Rutherford "received a call" from a

colleague. The first transatlantic phone call was made in 1927, so

that makes it quite impossible for a Copenhagen professor to have

called Rutherford while the latter was in Canada. I do not know if

telephony was possible between Copenhagen and Manchester in 1907-1911.

I do however know that it wasn't easy. Long distance calls at that

time required special booths. It seems immensely more reasonable that

Bohr's professor would contact a local physicist.

It's still a funny story. But come on: Give up the claim that it has

anything to do with Bohr or Rutherford. It doesn't.

Peter B. Juul / from Denmark / 27 November, 2008

***

Some time ago I received a call from a colleague. He was about to

give a student a zero for his answer to a physics question, while the

student claimed a perfect score. The instructor and the student agreed

to an impartial arbiter, and I was selected.

I read the examination question: "Show how it is possible to

determine the height of a tall building with the aid of a barometer."

The student had answered: "Take the barometer to the top of the

building, attach a long rope to it, lower it to the street, and then

bring it up, measuring the length of the rope. The length of the rope

is the height of the building."

The student really had a strong case for full credit since he had

really answered the question completely and correctly! On the other

hand, if full credit were given, it could well contribute to a high

grade in his physics course and certify competence in physics, but the

answer did not confirm this.

I suggested that the student have another try. I gave the student six

minutes to answer the question with the warning that the answer should

show some knowledge of physics. At the end of five minutes, he hadn't

written anything. I asked if he wished to give up, but he said he had

many answers to this problem; he was just thinking of the best one. I

excused myself for interrupting him and asked him to please go on.

In the next minute, he dashed off his answer, which read: "Take

the barometer to the top of the building and lean over the edge of the

roof. Drop the barometer, timing its fall with a stopwatch. Then,

using the formula x=0.5*a*t^2, calculate the height of the building."

At this point, I asked my colleague if he would give up. He conceded,

and gave the student almost full credit.

While leaving my colleague's office, I recalled that the student had

said that he had other answers to the problem, so I asked him what

they were.

"Well," said the student, "there are many ways of

getting the height of a tall building with the aid of a barometer.

For example, you could take the barometer out on a sunny day and

measure the height of the barometer, the length of its shadow, and the

length of the shadow of the building, and by the use of simple

proportion, determine the height of the building."

"Fine," I said, "and others?"

"Yes," said the student, "there is a very basic

measurement method you will like. In this method, you take the

barometer and begin to walk up the stairs. As you climb the stairs,

you mark off the length of the barometer along the wall. You then

count the number of marks, and this will give you the height of the

building in barometer units." "A very direct method."

"Of course. If you want a more sophisticated method, you can tie

the barometer to the end of a string, swing it as a pendulum, and

determine the value of g [gravity] at the street level and at the top

of the building. From the difference between the two values of g, the

height of the building, in principle, can be calculated."

"On this same tack, you could take the barometer to the top of

the building, attach a long rope to it, lower it to just above the

street, and then swing it as a pendulum. You could then calculate the

height of the building by the period of the precession".

"Finally," he concluded, "there are many other ways of

solving the problem. Probably the best," he said, "is to

take the barometer to the basement and knock on the superintendent's

door. When the superintendent answers, you speak to him as follows:

'Mr. Superintendent, here is a fine barometer. If you will tell me the

height of the building, I will give you this barometer."

At this point, I asked the student if he really did not know the

conventional answer to this question. He admitted that he did, but

said that he was fed up with high school and college instructors

trying to teach him how to think.

The name of the student was Niels Bohr." (1885-1962) Danish

Physicist; Nobel Prize 1922; best known for proposing the first

'model' of the atom with protons & neutrons, and various energy

state of the surrounding electrons -- the familiar icon of the small

nucleus circled by three elliptical orbits ... but more significantly,

an innovator in Quantum Theory.

|